Why is Britain funding Ghana’s Leftist, Russia-sympathising government?

A nation led by John Dramani Mahama is a bad port of call for this country’s global re-engagement policy

Source : The Telegraph

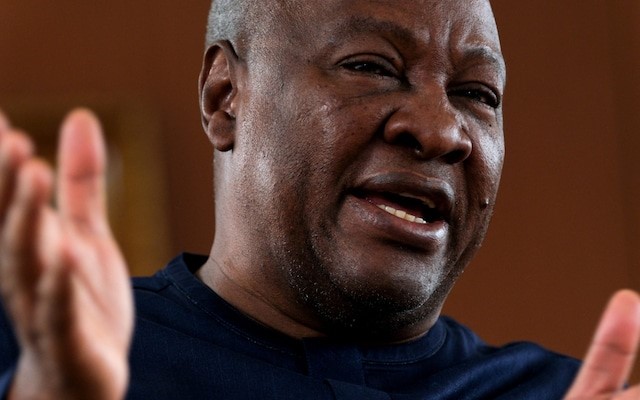

President John Dramani Mahama took office in January for a second non-consecutive term Credit: Francis Kokoroko

How far is too far in post-Brexit re-engagement with the wider world beyond Europe? Despite headlines about European resets, Labour has carried on the Tories’ project of flexing economic and diplomatic muscles from Africa to Asia that many thought had long atrophied.

Take Ghana. Most of the public think Britain’s global reconnect amounts to little more than the high-profile trade deals with the US and India – where Labour merely put the finishing touches on Conservative negotiations. But in the most sophisticated of West Africa’s nations, the UK is providing levels of economic assistance that would make the Chancellor’s forever repeated “guardrails” fall straight off any project back home.

Barely publicised beyond government websites, the UK has agreed to extend by 15 years the repayment period of $256 million Ghana owes Britain – and therefore ultimately the UK taxpayer. The deal also commits Britain to lending more on top to Ghana via UK export credits, underwriting British businesses to build a series of road and infrastructure projects across the country.

Ghana is not Somalia. It has long enjoyed a reputation for democratic governance. Still, in addition to owing $256 million to the British Exchequer, Ghana is also $261 million in debt to American independent power producers – liabilities ultimately underwritten by the US taxpayer. It is part of a whopping $2.5 billion the country holds in unpaid debts to energy suppliers alone.

One must question the common sense, let alone the economic case, of lending the country more. That becomes even more questionable when Ghana’s current government has begun demolishing the pillars of law and democracy on which the country’s good standing was built.

President John Dramani Mahama took office in January for a second non-consecutive term. Since then, Ghana has taken a far-Leftward, anti-democratic turn. Wielding lawfare against his political opponents, he has bent the law to protect his own. The chief justice of the Supreme Court was dismissed based on a “petition” that was never made public; half a dozen more compliant justices have since been appointed to the same bench. Scores of legal cases against members of the president’s own party, many related to serious fraud and a major banking collapse, have been dropped.

This approach should come as no surprise from a leader who is both a socialist and a Soviet sympathiser. His autobiography – My First Coup d’Etat – is partly set in Russia, a country where he studied and, by his own account, found quite agreeable. Mahama even took time out of last year’s election campaign to launch the book’s Russian edition in Moscow. Since returning to the presidency, he has made his mark on international affairs by penning an opinion article in The Guardian attacking Elon Musk and Donald Trump over South Africa.

But it is lawfare against the opposition that should most concern the money lenders in London. The most high-profile attack has been against Ken Ofori-Atta, the previous administration’s former finance minister.

Ofori-Atta is nothing if not a Western man. Educated at Yale and Columbia universities, he went on to work at Morgan Stanley and Salomon Brothers before founding his own investment bank. He became one of Ghana’s best-known and most successful international business leaders. Entering national politics only in middle age – and certainly not for the money – he went on to oversee major economic reforms of the banking system and steer the country through the strains of the pandemic, over a period during which Ghana’s GDP per capita nearly doubled.

Only days after Mahama’s return, the state turned on Ofori-Atta. Lurid accusations flew, followed by demands for his return to Ghana to face questioning. His home was raided; a special prosecutor branded him a fugitive from justice; US authorities were said to be processing an extradition request; and even an Interpol Red Notice was reportedly issued to extract him from the United States, where he was allegedly “hiding”.

Except he wasn’t. Ofori-Atta was in the United States receiving cancer treatment. Meanwhile, the military and police had entered his home in Ghana – apparently without a warrant. No extradition request was ever made to Washington; the special prosecutor has since admitted as much. Nor were there any indictments. The special prosecutor has never pressed charges – raising the question of whether Ghanaian authorities misled Interpol into issuing the Red Notice, which in law can only be applied after formal charges have been brought.

Nearly a year later, only salacious accusations have been made against Ofori-Atta, primarily about sign off on spending in government departments outside the finance ministry. It is the equivalent of expecting to hold Chancellor Rachel Reeves personally responsible for every single individual line item of spending in the Department of Culture, Media and Sport, or the Atomic Energy Agency, or the Passport Office.

It seems self-evident these attacks are underway because Ghana’s current leadership perceive Ofori-Atta – a man possessing presidential bearing – as a potential serious challenger at the next election, should he go down that path. This is no way to run a democracy. Indeed, it is questionable whether the rule of law is still functioning when such a stark case of political persecution is unfolding – and whether international businesses can still rely on the legal security of their investments in Ghana.

As for the British taxpayer, questions should be asked about whether this debt assistance amounts to good money being thrown after bad. Every British government should, of course, support British businesses working abroad. But there are simple calculations. Is there the rule of law? Is the legal system sufficiently independent? What are the chances of getting the money back? The answers are obvious, even to those of us who are not government economists. Ghana under Mahama is a bad port of call for Britain’s global re-engagement policy.