Nana Boakye Writes

A little over a year ago, Ghanaians went to the polls amid the heavy weight of economic turmoil triggered first by the global Covid-19 pandemic and then by Russia’s reckless and self-serving invasion of Ukraine. These two major external shocks severely disrupted what had been a growing and resilient Ghanaian economy, built on disciplined financial stewardship. The cedi had been relatively steady, and everyday citizens could afford basic goods and services.

However, the twin crises derailed this progress, forcing the government to rebuild the economy almost from the ground up. In order to revive growth, the administration rolled out a set of fiscal and economic measures, including the introduction of unpopular but in its view necessary taxes aimed at recovering revenues spent during the pandemic. In the process, many citizens seemed to forget how public funds had been used to protect lives during Covid-19. The President’s now-famous remark, emphasising that the economy could be revived later, but lives lost could not be restored, was suddenly forgotten.

The government’s attempt to introduce the electronic levy (E-levy) was meant to support a struggling economy. The opposition, however, capitalised on public frustration and mounted fierce resistance to the proposal, ultimately influencing many citizens to oppose it. Although the levy eventually passed in Parliament, the damage had already been done; large numbers of Ghanaians altered their mobile money habits, undermining revenue expectations and causing the policy to fall short. As a result, the economy continued to decline, with the cedi weakening rapidly, inflation soaring above 50 per cent, global oil prices rising, and gold and cocoa prices dropping. International credit rating agencies worsened the situation with unfavourable assessments. The opposition leveraged all of this to intensify public resentment toward the government.

IMF

Calls from civil society, commentators, and the opposition to seek help from the IMF grew louder, though the government resisted at first, hoping the E-levy would pay off. Once it became clear that the levy had failed, the administration reluctantly turned to the IMF. The resulting agreement came with tough conditions, including the Domestic Debt Exchange Program (the so-called “haircut”), which triggered outrage and protests, some led by prominent national figures like a former Chief Justice. Meanwhile, other contentious national issues, including illegal mining, LGBTQ+ debates, and the National Cathedral discourse, further complicated matters, providing additional fuel for the opposition.

The opposition accused the government of failing to tackle illegal mining due to the alleged involvement of its own members. Some even promised to eradicate galamsey within two weeks if given power. They collaborated with elements of civil society, the media, and unions, including some university lecturers, to discredit the government. At the same time, they privately encouraged illegal miners to continue, claiming unemployment left them no choice but to mine. Accusations of corruption escalated, ranging from the presidential jet debate to attacks on secondary school feeding programs. According to this narrative, truth was drowned out by a coordinated campaign of misinformation and propaganda.

As tensions heightened approaching the December election, the cumulative pressure and negative sentiment eventually led to a heavy electoral defeat for the New Patriotic Party (NPP), giving the opposition a commanding majority in Parliament.

Fast forward: initiatives begun in 2023 and 2024, such as the gold-for-oil policy, gold purchases, and increased import reserves, began bearing fruit by 2025 as the effects of Covid and the Ukraine conflict subsided. Yet instead of continuing with innovation-focused programs like TVET, STEM, and digitalisation, the new government shifted focus to less transformative policies, including “nkukor nkitinkiti,” okada licensing, and the promise of a 24-hour economy, which was marketed as “three people sharing one job. (3-3-1)”

One year into its term, the new administration appears to rely on its overwhelming majority to pass legislation unquestioned, while using the courts to reclaim seats from the opposition under the guise of election petitions.

The Judiciary

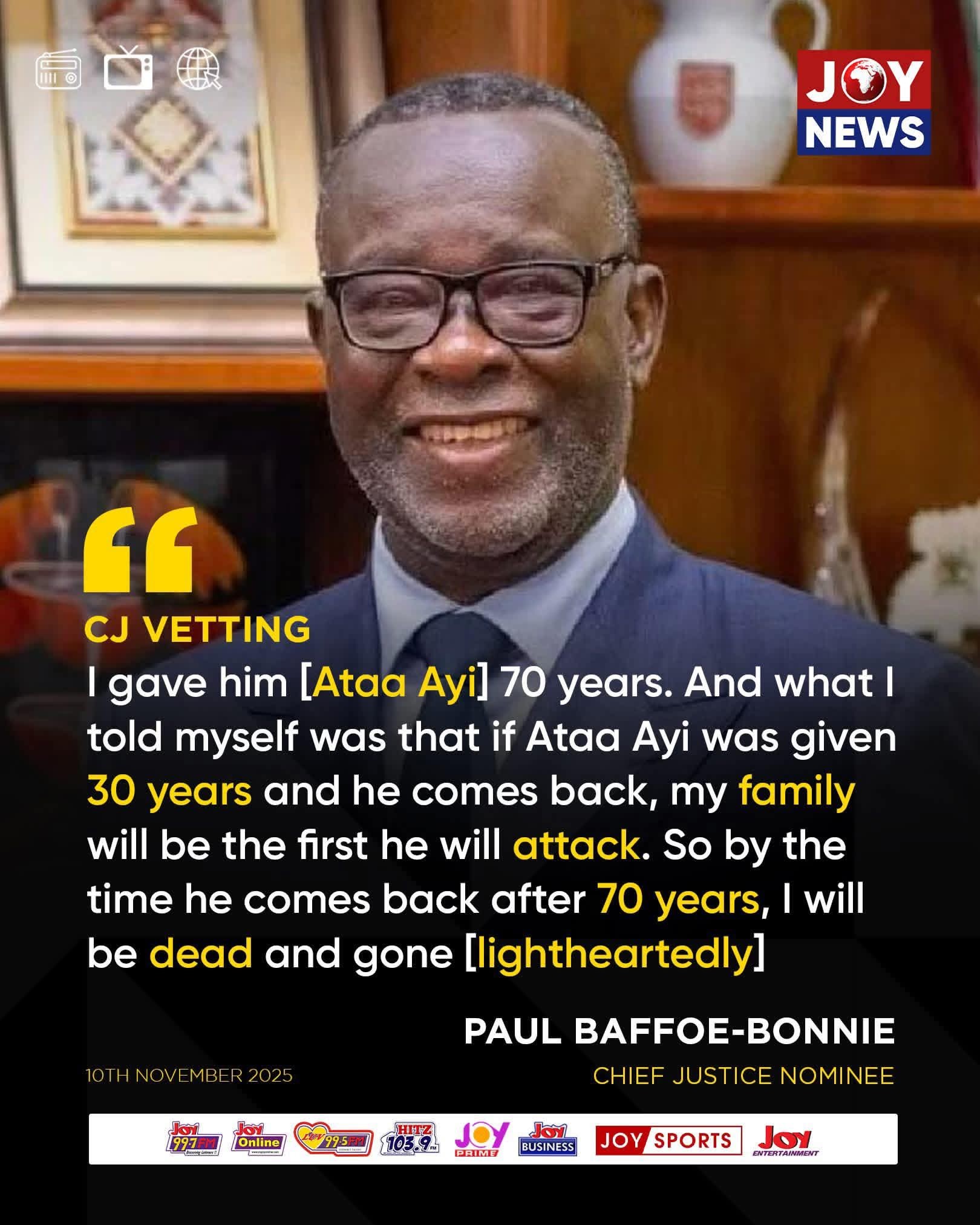

In opposition, they vowed to remove the Chief Justice (CJ) if they came to power, and they followed through quickly, orchestrating a petition and using Article 146 procedures to remove the CJ. A new one was hastily approved by the supermajority. Subsequently, dozens of new judges were appointed. Before this judicial overhaul, the Inspector General of Police (IGP) and Chief of Defence Staff (CDS) were also replaced, with senior officers pressured to step down, effectively placing institutions meant to remain independent under government control. Civil society groups, sections of the media, academia, religious leaders, and even traditional authorities have also been compromised.

Despite all these powers, the administration has spent its first year focused more on pursuing political adversaries and attempting to uncover wrongdoing than on governance. After twelve months, many view the government’s performance as a major disappointment, obscured only by self-congratulatory claims about stabilising the cedi.

The question, therefore, being asked is: One year on, where are we?

For now, Ghana must endure this administration until voters hopefully restore the New Patriotic Party to power.

Merry Christmas.