Kwame Baffoe, better known as Abronye DC, has shaken the nation with his asylum application abroad. His claim that he is unsafe in his own country is not only disturbing, but it also forces us to reflect on Ghana’s long struggle with political freedom.

We have been here before. In 1979, Jerry Rawlings led the Armed Forces Revolutionary Council (AFRC) in a coup that promised accountability but ended in brutal executions and widespread fear. In 1981, Rawlings struck again, ushering in a decade of military dictatorship under the PNDC where opposition voices, journalists, and activists faced arrests, torture, and exile. Those who dared to speak out often disappeared, and many sought asylum abroad.

It took the 1992 Constitution to finally restore multiparty democracy. Since then, Ghanaians have prided themselves on peaceful elections and respect for rights. But Abronye’s case suggests that old habits are creeping back: security agencies leaning on political opponents, intimidation replacing dialogue, fear where there should be freedom.

This should alarm us. If, after nearly 45 years since 1979, Ghana still struggles to guarantee opposition voices safety, then our democracy is more fragile than we admit. Today it is Abronye; tomorrow, it could be any Ghanaian who dares to disagree.

We must remember our history and refuse to repeat it. Leaders must act to restore trust, and the police must serve the people—not the party in power. Otherwise, the sacrifices of 1979 and the gains of 1992 would have been in vain

Ghana Risks Repeating the Mistakes of 1979

Ghana’s reputation as a model democracy in Africa is once again under scrutiny. The asylum application by opposition politician Kwame Baffoe, widely known as Abronye DC, is more than an individual complaint—it echoes a history of political intolerance stretching back to the late 20th century.

In 1979, Ghana underwent a violent military coup led by Jerry Rawlings, whose regime executed senior officials and curtailed dissent. A second coup in 1981 entrenched authoritarian rule for over a decade, driving many activists, journalists, and politicians into exile. Only with the 1992 Constitution did Ghana re-enter the path of multiparty democracy, winning international praise for stability and free elections.

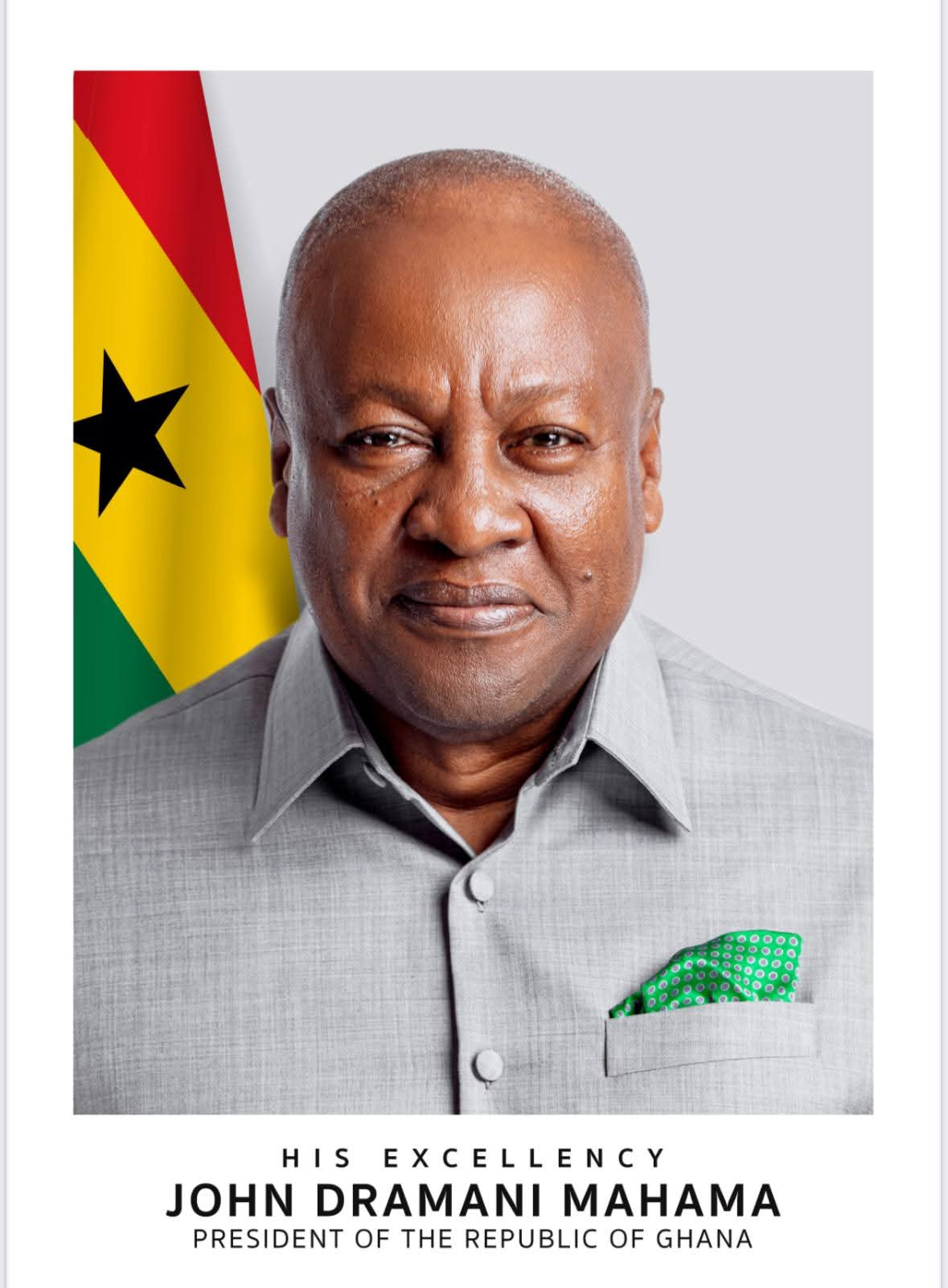

Yet the allegations raised by Abronye—that security agencies are being deployed against opposition figures under President John Mahama—suggest that the old shadows have not fully disappeared. Political asylum applications by opposition figures evoke memories of a darker era when free expression could cost lives.

Ghana now faces a critical choice. Either it protects its democratic legacy, built painstakingly since 1992, or it risks sliding back toward the repressive patterns of 1979 and 1981. The international community should watch closely, but it is ultimately Ghana’s institutions—its judiciary, its police, its political leadership—that must decide whether dissent is a right or a crime.

For a nation long celebrated as a beacon of democracy, this is a moment of truth. The lessons of 1979 must not be forgotten.