For decades, the Ghana Cocoa Board (COCOBOD) has stood as the backbone of Ghana’s economy ,a stabilising force for cocoa farmers and a major source of foreign exchange for the state. Today, that backbone is cracking.

The warning did not come from critics or opposition figures. It came from the very top.

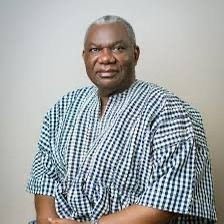

Earlier this week, COCOBOD’s Chief Executive Officer, Mr. Ransford Abbey, aka Randy Abbey publicly admitted that the Board is currently unable to purchase cocoa beans from Ghanaian farmers because the local producer price is now higher than international market prices and those of neighbouring cocoa-producing countries. Falling global prices, he explained, have made Ghana’s cocoa “too expensive.”

It was a statement that landed like a thunderbolt across the cocoa sector.

When a Cocoa Board Cannot Buy Cocoa

COCOBOD exists for one core reason: to buy cocoa from farmers, market it globally, and protect the sector from price volatility. Its inability to perform this function strikes at the heart of its relevance.

Industry observers argue that the CEO’s admission amounts to a declaration of institutional paralysis. If COCOBOD cannot buy cocoa during peak season, farmers are left exposed, incomes are threatened, and the entire supply chain is destabilised.

For farmers already battling rising fertiliser prices, climate shocks, and inflation, the announcement has deepened uncertainty. “If COCOBOD steps back, who protects us?” one farmer leader asked. “That is how smuggling and exploitation begin.”

A Tale of Two Realities

Even as farmers face delayed purchases and income insecurity, troubling revelations have emerged about COCOBOD’s spending priorities.

According to Mr. Fifi Boafo, former Public Relations Officer of COCOBOD, the institution has recently acquired more than four Toyota Land Cruisers and over 100 Toyota and Nissan pickup vehicles at a cost exceeding GH¢20 million.

The disclosure has ignited public outrage.

To critics, the contrast is glaring: an institution pleading poverty when it comes to buying cocoa, yet displaying financial muscle when it comes to executive comfort and fleet expansion.

The optics are devastating. “You cannot tell farmers there is no money, then turn around and spend millions on luxury vehicles,” an industry analyst remarked. “It speaks to distorted priorities.”

The Farmer Pays the Price

When COCOBOD cannot buy cocoa, farmers do not simply wait patiently. The vacuum is quickly filled by smugglers and middlemen offering cash across porous borders. Every bag smuggled out represents lost foreign exchange, reduced government revenue, and weakened national reserves.

This is not hypothetical. Ghana has lived through it before.

Experts warn that COCOBOD’s current stance risks reopening the floodgates of cocoa smuggling, particularly into Côte d’Ivoire, where price differentials can be exploited.

More Than a Cash Problem

Beyond liquidity constraints lies a deeper question of governance.

Is COCOBOD facing a temporary cash-flow challenge, or has it been weakened by years of debt accumulation, inefficient procurement, and poor fiscal discipline? Why were vehicle purchases prioritised over cocoa purchases? Were these procurements budgeted, approved, and aligned with a broader financial recovery plan?

These are questions yet to be answered.

What is clear is that cocoa is not just another commodity. It is a strategic national asset. Decisions taken at COCOBOD reverberate through rural livelihoods, export earnings, and macroeconomic stability.

An Institution at a Crossroads

Civil society groups and farmer associations are now calling for an independent audit of COCOBOD’s finances, procurement decisions, and debt obligations. There are growing demands for parliamentary oversight and ministerial intervention.

Some voices are going further, arguing that leadership accountability must be placed squarely on the table. When an institution charged with protecting farmers cannot perform its primary duty, consequences must follow.

The Cost of Inaction

If this crisis is mishandled, the damage will extend far beyond COCOBOD. Trust between farmers and the state will erode. Smuggling will rise. Export revenues will fall. And Ghana’s reputation as a reliable cocoa supplier will suffer.

COCOBOD once symbolised stability in an unpredictable global market. Today, it risks becoming a symbol of mismanagement and misplaced priorities.

The choice before policymakers is stark: reform decisively and restore confidence, or preside over the slow collapse of one of Ghana’s most important institutions.