Investigative Desk Report

A fast-moving dispute over the Black Volta Gold Mine in Ghana’s Upper West Region is raising serious legal, financial, and governance concerns—just days after the ECOWAS Bank for Investment and Development (EBID) signed a $181 million agreement tied to the contentious project.

At the heart of the storm is a bitter feud between Australian investors Ibaera Capital and Engineers & Planners (E&P), a Ghanaian contractor linked to presidential family interests. The fallout is already reverberating through West Africa’s development finance community and drawing attention to possible institutional lapses at the highest levels.

Unraveling the Gold Deal

In 2021, E&P entered into an agreement with Azumah Resources and its private equity backer Ibaera Capital to earn a stake in the Black Volta gold project by fulfilling several conditions, including paying $181 million by June 30, 2024, executing an engineering procurement contract (EPC), and raising debt financing with Ibaera’s consent.

But Ibaera alleges E&P failed to meet those terms. Specifically, they accuse E&P of missing the payment deadline, unilaterally appointing directors to project companies, and taking control of corporate bank accounts and commercial negotiations without legal authority.

In response, E&P initiated arbitration proceedings in London under ICC rules, accusing Ibaera of obstructing their financing efforts and acting in bad faith. Ibaera, however, argues that the claims are vague and contradicted by hard contractual terms.

EBID’s Controversial Entry

Despite this unresolved arbitration, EBID signed an agreement on July 7 to fund the exact same $181 million required under the now-contested E&P deal. The precise identity of the counterparty to EBID’s agreement remains murky. If EBID signed with E&P, the transaction may be invalid under Ghanaian and Australian law—given that Ibaera still controls Azumah Ghana, the mine’s legal owner. If the agreement was with Azumah, questions arise as to whether E&P had authority to bind the company.

Two Ghanaian public officials, Noel Nii Addo of SSNIT and Nana Dwemoh Benneh of Ghana Infrastructure Investment Fund (GIIF), signed off on the EBID deal as directors—despite ongoing legal challenges and without apparent project board approval. Their dual roles as public servants and E&P-aligned directors raise potential conflicts of interest.

MDB Governance in Question

Unlike institutions such as the African Development Bank or World Bank, EBID has not published environmental assessments, financial due diligence, or board deliberations for the transaction—sparking criticism about transparency and governance standards.

“This is a risky deal,” one development finance expert said on condition of anonymity. “You have a terminated agreement, an ongoing arbitration, and no clarity on who actually controls the asset. EBID’s involvement defies basic prudence.”

Compounding concerns is EBID’s past exposure to E&P. The bank previously restructured a distressed loan to the company in 2023—raising eyebrows over why it would reengage in a much larger, riskier transaction.

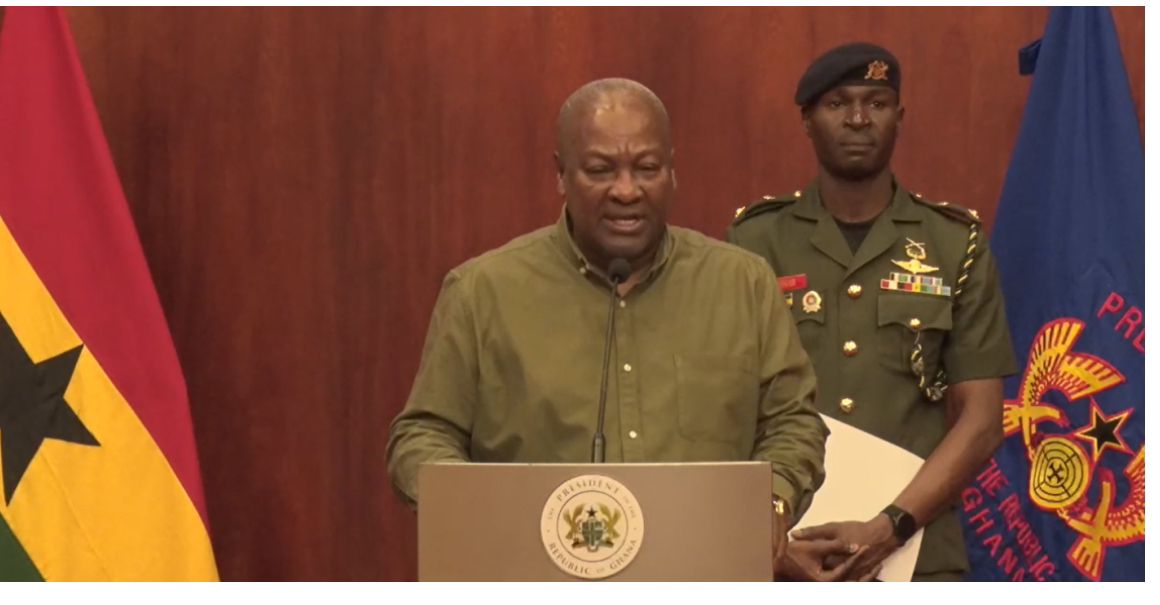

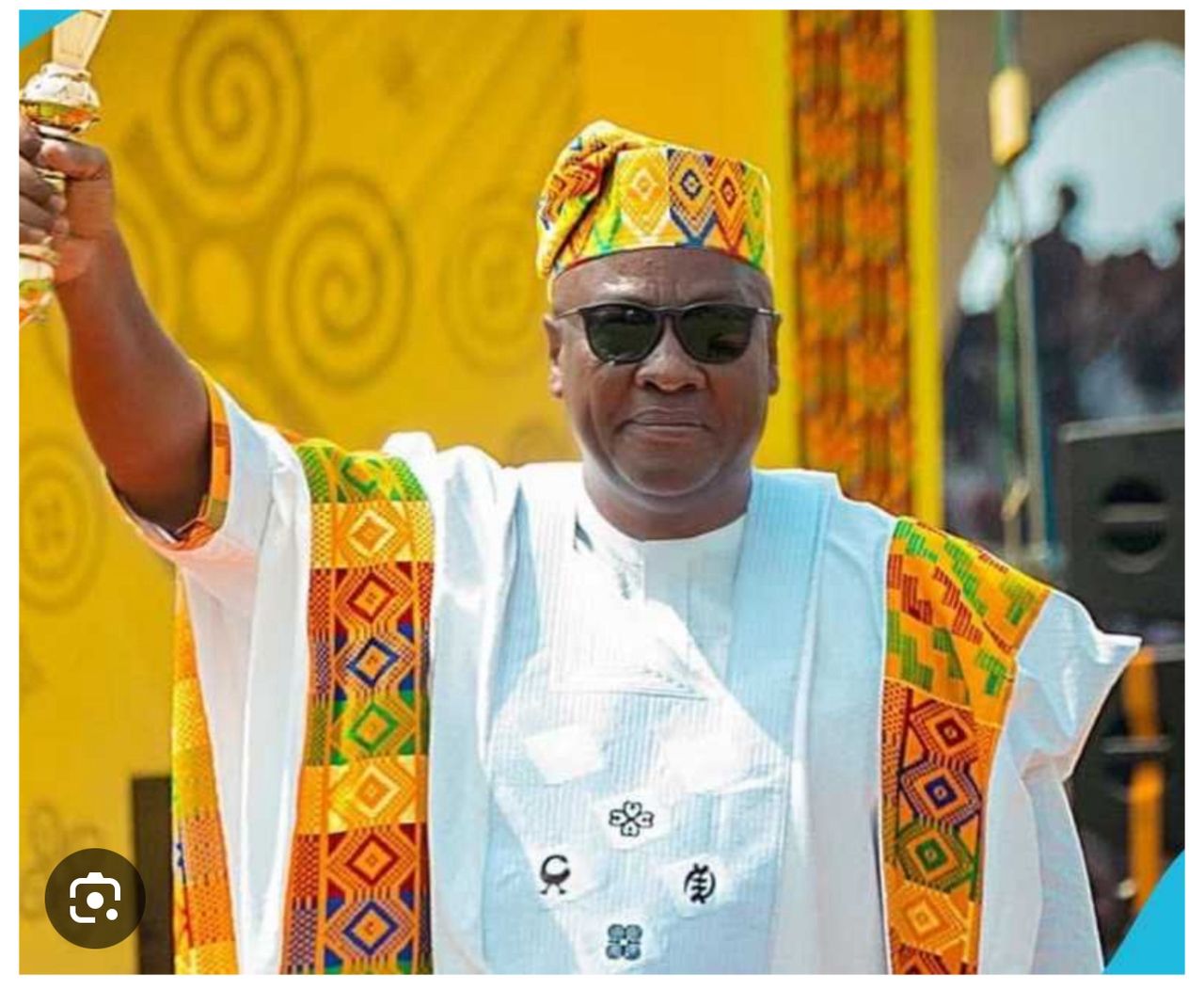

Political Shadows

The affair is also entangled in politics. E&P was founded by Ibrahim Mahama, the brother of Ghana’s President, and several officials involved in the project are known political appointees.

Sources close to the matter suggest the President is being urged to intervene to prevent a full-blown governance scandal that could impact Ghana’s investment climate and EBID’s credibility as a regional financier.

“There’s too much at stake—for the rule of law, for development finance, and for Ghana’s reputation,” one legal analyst observed.

Gold Rush Meets Legal Quagmire

With gold prices surging, the Black Volta Mine project—estimated to hold 1.65 million ounces of gold and a projected 11-year life—is a potential economic windfall. Ibaera has reportedly spent over $40 million de-risking the project and claims E&P’s alleged misconduct puts that at risk.

While both sides remain locked in arbitration, the EBID deal has introduced a volatile new variable—one that could draw scrutiny from ECOWAS, investors, and governance watchdogs alike.

Key Questions Remain:

Who exactly did EBID sign with?

Was proper legal authority obtained?

Did EBID assess the project’s litigation risk?

What governance procedures were followed?

Will the Ghanaian government intervene?

The story is developing.